At Rodeo Drive Plastic Surgery, in addition to the usual cosmetic surgery procedures such as Los Angeles tummy tuck and

breast augmentation, we also provide innovative breathing surgery.

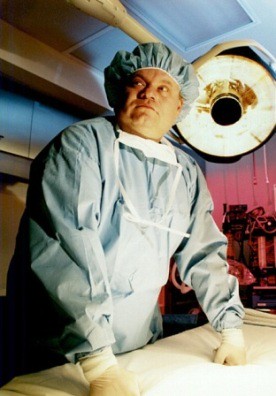

Below are excerpts from two articles about a unique procedure to help people previously confined to a ventilator for life. The research behind the procedure and its development was done by Abbott Krieger, MD, the father of our Medical Director. Dr. Abbott Krieger did basic research on the concepts for this revolutionary surgery. He then pioneered its use clinically. The procedure uses a nerve transfer technique to allow the phrenic nerves to once again stimulate the diaphragm to move air, allowing patients to breathe without the need for a ventilator.

From New Scientist---

PEOPLE who face spending the rest of their lives on ventilators may be able to breathe on their own again with the help of a new surgical technique.

To help people breathe normally when they're disabled by spinal cord injuries, surgeons often implant a pacemaker that stimulates the phrenic nerve, which cues the diaphragm's breathing motion. But this doesn't work if the nerve has also been damaged. Now Abbott Krieger, a neurosurgeon in Livingston, New Jersey, says that he can repair phrenic nerves so they respond to the pacemaker.

Abbott Krieger MD takes a nerve that goes to a chest muscle and grafts it on to the dead phrenic nerve. After a few months, he says, the phrenic nerve becomes functional again and the pacemaker works—so the patient can live without a respirator.

Neurosurgeons use this type of nerve grafting to repair more peripheral nerves such as those in the face, but never in the deep chest cavity where microsurgery is difficult. Krieger's procedure was successful in five out of the six patients he treated, he told the Congress of Neurological Surgeons in Boston this week.

From Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery---

The Intercostal to Phrenic Nerve Transfer: An Effective Means of Reanimating the Diaphragm in Patients with High Cervical Spine Injury

Nerve transfers have been well described for the treatment of congenital and traumatic injuries in the brachial plexus and extremities. This series is the first to describe nerve transfers to reanimate the diaphragm in patients confined to long-term positive pressure ventilation because of high cervical spine injury. Patients who have sustained injury to the spinal cord at the C3 to C5 level suffer axonal loss in the phrenic nerve. They can neither propagate a nerve stimulus nor respond to implanted diaphragmatic pacing devices (electrophrenic respiration).

Ten nerve transfers were performed in six patients who met these conditions. The procedures used end-to-end anastomoses from the fourth intercostal to the phrenic nerve approximately 5 cm above the diaphragm. A phrenic nerve pacemaker was implanted as part of the procedure and was placed distal to the anastomosis. Each week, the pacemaker was activated to test for diaphragmatic response. Once diaphragm movement was documented, diaphragmatic pacing was instituted.

Eight of the 10 transfers have had more than 3 months to allow for axonal regeneration. Of these, all eight achieved successful diaphragmatic pacing (100 percent). The average interval from surgery to diaphragm response to electrical stimulation was 9 months.

All patients were able to tolerate diaphragmatic pacing as an alternative to positive pressure ventilation, as judged by end tidal CO2 values, tidal volumes, and patient comfort. Intercostal to phrenic nerve transfer with diaphragmatic pacing is a viable means of liberating patients with high cervical spine injury from long-term mechanical ventilation.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

This blog reviews the latest trends in plastic surgery directly from the world's most prestigious address in cosmetic surgery -- Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, California.